1. Introduction

The present era of advanced technology and constant digitization, which has added ease to our fast-moving life, is no longer unaware of the transition from physical work to digital. The new form of digital labour in the modern capitalist economy is hard to detect in the conflation and blurring of lines between production and consumption (Roy 2015). With the entry of these digital aspects into our new lifestyles becoming pivotal, it has impacted the education field also, visible in the transformations in “labour processes” in academics in the last few decades (Woodcock 2018) and the recent shift of humanities into a new, multidimensional, diverse field of digital humanities (DH) (El Khatib et al. 2021). This new form of labour, however, does not easily fit with traditional notions of the humanities; consequently, we must find different ways to detect, define, and compensate this labour.

Being that digital humanities is a new interdisciplinary area that has different methodologies and practices of research vis-à-vis traditional humanities, it is incumbent to make these methodologies and practices visible to define substantive contributions and consequently reward or compensate that work. While it is exciting and attractive to think of incorporating new technologies and methods to further humanities research with possibilities of new insights, the multi-pronged effort required for this work is often not visible. DH interestingly combines the thinking, writing, and doing elements of traditional humanities inquiries; nevertheless, the traditional humanities, while embracing this promising new discipline, has overlooked the immense labour that comes with it. The new openness, which promises to build “commons” or meaningful public spheres, is threatened by old exclusionary notions. Though there are talks about the introduction of new ideals in DH—collaboration in place of individualistic activities, openness, and dynamicity in humanities work—they have hardly shaken the core pillars of traditional humanities that have taken decades to establish (El Khatib et al. 2021). These values are in complete contrast to the recognition or privileges given in reality with the “one-author/one-work” policy (Nowviskie 2011). The perspective and the evaluation method of the traditional system need to be reconsidered; for instance, the double work done by students in the field of DH is no longer unknown, yet researchers are still expected to accomplish a wide range of works singlehandedly (Boyles et al. 2018). Though the experts’ involvement in labour is often acknowledged, in Boyles and colleagues’ words, “this is not always the case,” prompting our present research (Boyles et al. 2018, 695). While the methods and ideals of DH are much appreciated and celebrated, the concern for digital labour as a huge add-on to the process is all too set to claim substantial amount of space in academia.

Since digital labour (DL) and academia are both vast fields, in our paper, we are narrowing it down to DH. Despite the ideals that characterize the field of DH—teamwork/collaboration, open-access, inclusion, flexibility, etc. (Anderson et al. 2016)—the labour part is often unrecognized; in the Indian context, struggling with the lack of resources (especially considering the nascent stage of DH), the labour is huge. Our paper thus focuses on DL in DH in the Indian context. In this paper, we consider DL that is carried out in academics, especially in DH projects from or based in India. In an attempt to locate or define DL in DH, we found DL mostly “understudied” in academia (Woodcock 2018, 131) and “undertheorized” in DH (Presner et al. 2009, cited in Anderson et al. 2016), hence lacking a proper definition. Therefore, we are trying to understand the presence, acknowledgment, and compensation of DL in DH in the Indian academic space, along with a review of existing formats/frameworks to document DL. As part of our methodology, we have undertaken case studies of selected DH projects from India. Along with the responses received via Zoom-based, semi-structured interviews, the websites and social media handles of the DH projects are also explored. The thematic categorization of findings from the process contributes to both unpacking the causes behind the tediousness of the labour and the identification of the digital labourers (DLers) involved in the project. The analysis further enabled us to propose a plausible framework to define, detect, and compensate DL in DH. This study proposal is a work in progress that aims to initiate discussions on DL in DH by focusing specifically on the DL involved in the development, dissemination, and maintenance of DH projects. The proposal will further help the academics in the field to think about better ways to both acknowledge and compensate the same.

2. Background: Digital labour in digital humanities

According to the Cambridge Dictionary, the term labour has different meanings based on the part of speech that it refers to, that is, as a verb—the act of labour itself, “the practical work, especially when it involves hard physical effort”—or as a noun—the one who does the action, “workers, especially people who do practical work with their hands.” DL, in contrast to manual labour (ML), has been used in contemporary scholarship “to describe a huge variety of activities: clickwork done in people’s homes, call-centre work in large offices, editing a Wikipedia article, and even uploading a photograph to social media from a phone” (Graham and Anwar 2017, 2). DL in the academic context, however, is a much more complex interaction between academic labour and digital technology, the mastery of which imposes additional pressure on the students and academicians to excel in both the areas (Jones 2010). Nevertheless, the academic DL “remains in the background,” “far removed from the day-to-day activities of academic labour on which universities rely” (Woodcock 2018). In the context of this paper, we consider DL that is carried out in the academic context, especially the DL by DH scholars and students in India while developing DH projects.

The scholars of DH are expected to be eligible for diverse activities and to play multiple roles efficiently, but their positional limitations in DH works are bound to obstruct their holistic growth (Boyles et al. 2018). The ideal of DH supporting the activities of “co-creation and teamwork” has paved the way for student labour, which is “largely undertheorized in DH literature” (Presner et al. 2009, cited in Anderson et al. 2016). The structural/hierarchical division evident in the field disqualifies the field’s opposition against its traditional form (Anderson et al. 2016) and makes visible the problematic labour. Students as “unseen collaborators” do the preliminary work of the DH projects, which are mostly undervalued and pushed down in the hierarchical division of productive labour. While the racial and geographical exclusivity of DH has already been there (Mahony 2018), the literature review undertaken explains the internal divisions in the field in terms of roles, levels, and academic hierarchy (Anderson et al. 2016; Mann 2019). A neoliberal perspective in the field of DH privileging collaboration over individual activity, which ideally refers to working on a common stage with equal participation, in reality suggests “formally structured research relationships” (Mann 2019, 1).

The “unlikely pairings” in DH through collaboration are supposed to germinate new insights from the literary texts, as this collaboration works “laterally” in expanding across disciplines as well as “vertically” in collating all hierarchical positions on the same platform (Anderson et al. 2016). But according to the survey results by Anderson and colleagues (Anderson et al. 2016), this ideal engagement that is expected greatly differs in real-time scenarios where the students/scholars are not given equal opportunities to publish about the project’s matter/outcome. Formal academic publishing is often used to boost researchers’ potential reach, as well as their belief in their own capabilities. Nevertheless, the simple acknowledgements section on any research project’s website, as well as the absence of similar recognition in published work, exposes the degree to which these achievements are scaffolded by the labour of others, especially those further down the academic ladder. Again, collaboration has always been looked down upon, valuing only single-authored works in humanities scholarships. Some of these inequities come from pressure in traditional humanities where collaboration is not natural, good practice. Thus, though the field transcends the boundaries of traditional publishing, publishing values have not shifted alongside. Publishing infrastructures go on prioritizing the single-authored works that “continue to represent the field” (Mann 2019, 3). Scholars remain traditional humanists, all the while calling themselves digital humanists. The core values of the humanities have remained the same even though they shifted to digital (Cohen, Ramsay, and Fitzpatrick 2013; McGann 2014; El Khatib et al. 2021).

Also, the library, which poses as a vital partner and has a central role in humanities scholarship, has transformed its structures and responsibilities for supporting the DH projects. With this shift in status and means of support, the labour and the importance that have long been invisible in the production of knowledge in traditional humanities have become manifold in DH. The “support labour” by the librarians has shifted from “traditional library work” to “DH projects” (Braunstein 2017, 3). Thus, Kim’s witty address to the concern by calling the labourers “miracle workers” was soon adopted by many (Kim 2017). Our paper thus queries the foundation of the emerging digital field, which attunes itself to notions of capitalism and neoliberalism in hiding the transformation and precarity of labour (Woodcock 2018, 137). The reorientation, transformation, and several shifts that academia has gone through made labour in academic work hidden and invisible. Again, the metrics, rankings, and comparisons that intensify the labour are invisible forms of control, leading the researchers to “auto-precarization” (Montoya and Perez 2016, cited in Woodcock 2018). Thus, the greater possibilities in DH with the intermediacy of digital technologies come with the precariousness of labour.

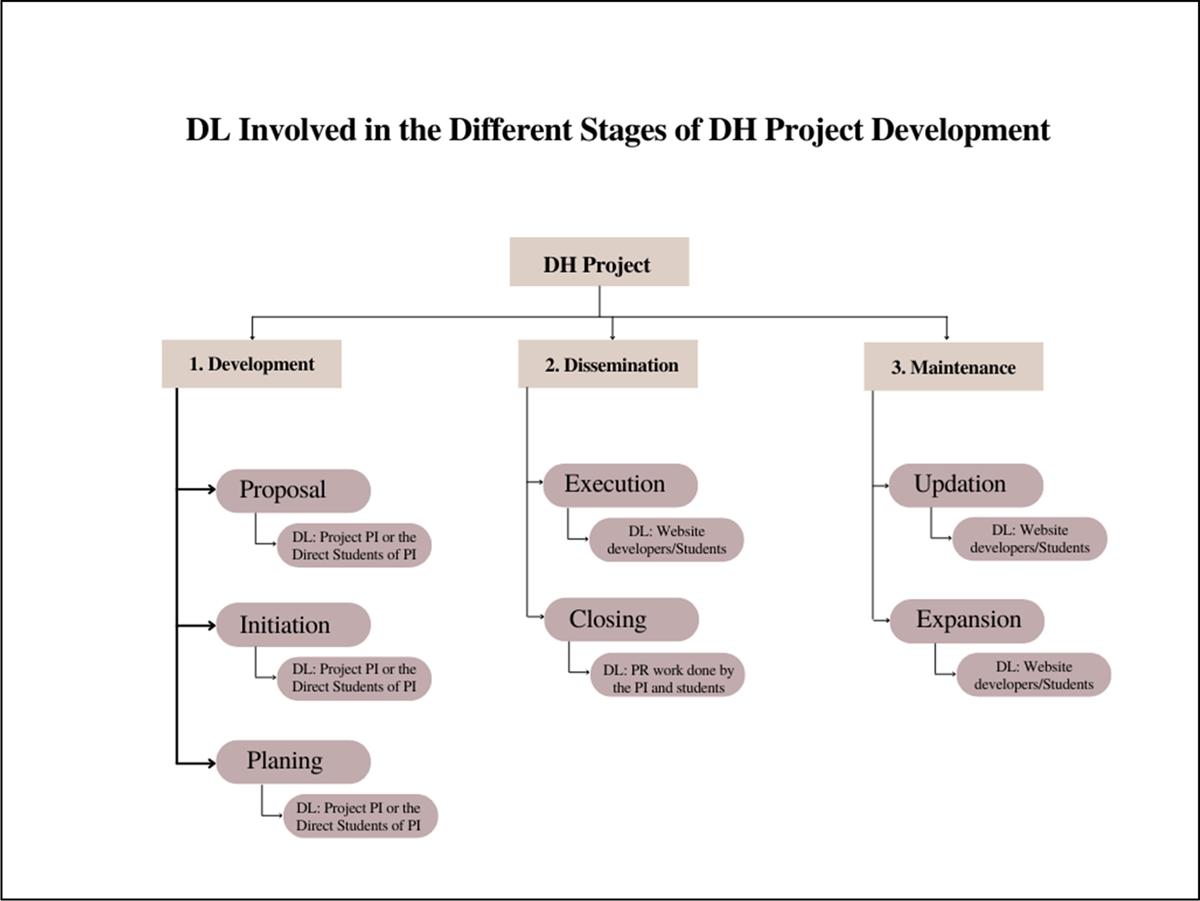

Anderson and colleagues claim that student labour and training are highly “undertheorized” in DH (Presner et al. 2009, cited in Anderson et al. 2016). Since students constitute the majority of DLers in DH, it is important to look at their work from both academic (pragmatic in the form of credits and acknowledgments) and theoretical (definition and structure) frameworks. The lack of a proper definition of DL in DH and the subjectivity and dynamic nature of the DL involved in DH projects are some of the factors that further make the identification and classification of DL in DH even more difficult. However, in order to theorize on DL in DH, we first need to understand and look deeply into the practical components of DH, which include teamwork/collaboration, open access, inclusion, and flexibility from its initial stages; the labour part is always invisible when it comes to the actualization of these (Anderson et al. 2016). Based on the components of DH, the DL involved in DH projects broadly occurs in three stages: 1. development, 2. dissemination, and 3. maintenance. The Project Management for the Digital Humanities (PM4DH) (ECDS Team and LITS PMO Team 2022), a guide to DH project management developed by the Emory Center for Digital Scholarship, proposes five phases for a DH project lifecycle: “proposal, initiation, planning, execution, and closing.” The first three phases belong to the developmental stage, and the last two are in the dissemination phase. This broad classification of DH projects into three stages does not strictly follow any boundaries, as we acknowledge that each stage could merge with another, and often the activities of each stage are not clearly distinguishable. The different stages of the DH project and the DL involved in each phase of the stage can be visualized, as seen in Figure 1.

The DL at each stage of the development of a DH project should be properly documented to compensate for the same in the most appropriate manner. The development stage of a DH project consists of DL in the form of evaluating the strategies for the project setup, data collation, etc., and therefore usually requires more DL. The developmental stage of the DH project consists of the proposal, initiation, and planning phases (ECDS Team and LITS PMO Team 2022). In the proposal, initiation, and planning phases, much of the work gets done by the PI or the direct students of the PI. In the initiation phase, the work consists of “crafting a proposal, whether formal or informal, to showcase the project’s potential and to attract the support and resources necessary to tackle it,” as well as designing the project; in the initiation phase, drawing up “a detailed project charter and assembling a team capable of managing the multiple facets of a digital humanities project” is attempted (ECDS Team and LITS PMO Team 2022). The planning phase consists of setting “appropriate boundaries” for the project in the form of defining the scope of the project and the budget limits (ECDS Team and LITS PMO Team 2022). The labour involved in these phases is often regarding the set-up of the project, which could be done digitally or otherwise. However, digital documentation of these early steps will help not only to shed light on the DL involved, but also to serve as a reference for future projects.

The dissemination stage comes in the form of deliverables, “a website, blog post, book, presentation, workshop, publication, virtual exhibit, code, digitized materials, or service” that can further the engagement with the DH project (ECDS Team and LITS PMO Team 2022). The dissemination stage consists of both the execution and closing phases. The execution phase tends to merge within the developmental and the dissemination stages of DH project management, as it involves the creation of a proper work plan with the distribution of duties and confronting or resolving the problems that might arise. The execution phase also consists of publicizing the result of the project in the form of deliverables. The DL involved in this stage is mostly carried out by the IT departments or is outsourced to we-developers who are assigned specific duties on the project as well as to create the final deliverables. Interestingly, due to lack of funding, the deliverables of Indian DH projects are often performed by the students themselves, who must train to achieve the same. This phase also consists of public relations performances where the PI and the students are expected to create connections with others in the field to receive funding, collaborative opportunities, etc. The closing phase consists of “delivering the deliverables, finalizing paperwork, and evaluating both the project and team members.” The closing documentation, including the failures and successes of the project, is attempted. The maintenance stage, which is now discussed here, is ignored by the PM4DH (ECDS Team and LITS PMO Team 2022). This stage mostly caters to the sustainability of the project, which means that there will be manual work in the form of maintaining the website, data updating, and backup done periodically by the DLs, mainly students: “Realistically, the maintenance of inactive or archived projects will fall to a staff member at an IT department, the institution’s library, or a DH centre who juggles maintenance for a portfolio of projects alongside their day-to-day responsibilities” (Boyles et al. 2018).

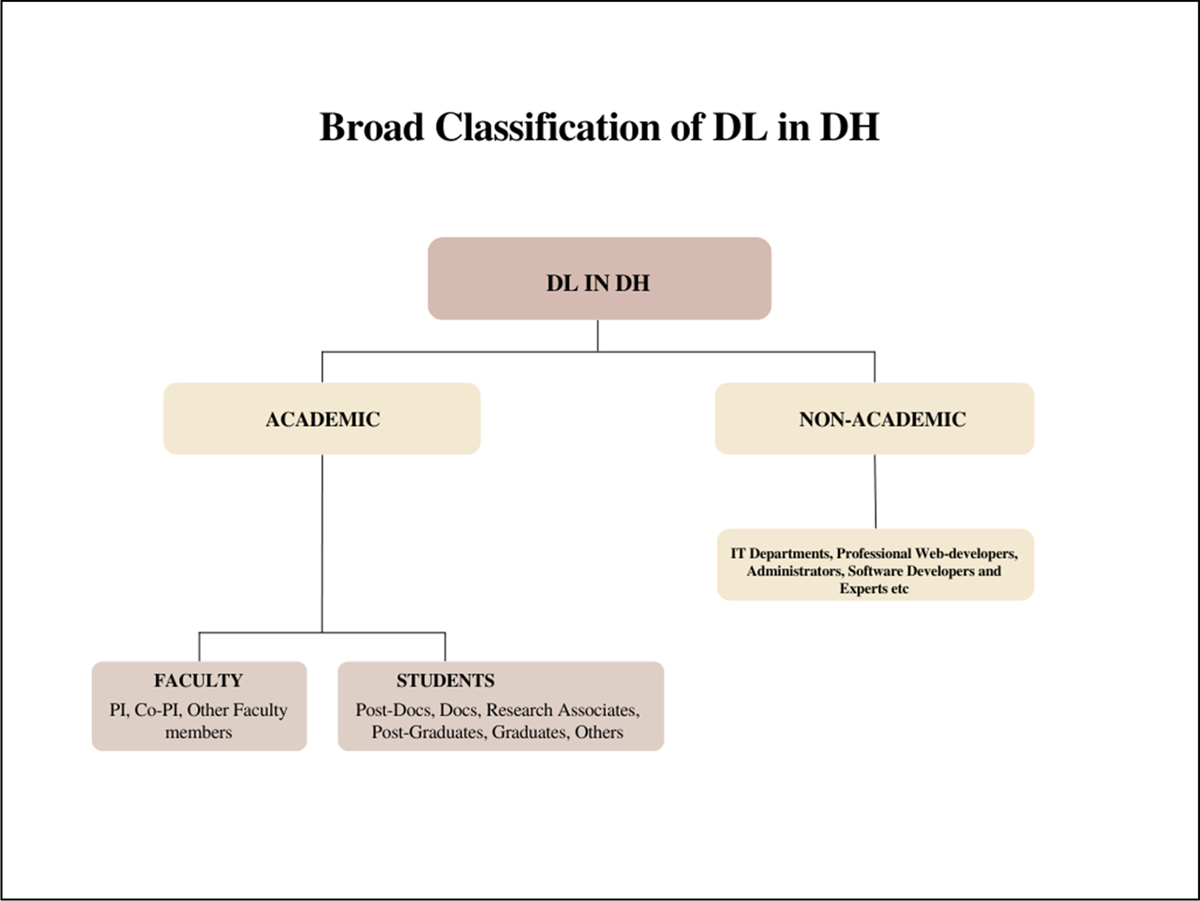

The lack of an accepted definition for DL in DH makes it important to identify and classify the same. In the literature review conducted for this study, we found a mention of the DL in DH in the work of Kim, who referred to the DLs as “miracle workers,” owing to the amount of free labour that is expected of DH practitioners who “perform as scholars, tech support, administrators, project consultants, and more” (Kim 2017). Boyles and colleagues, similarly, identify the DLers in DH as “administrators, adjuncts, postdocs, graduate and undergraduate students, tenure-track and contingent faculty, librarians, archivists, programmers, IT and edtech specialists, consultants, museum curators, artists, authors, editors, and more” (Boyles et al. 2018, 693). They also point out that DL in DH is “precarious” (Boyles et al. 2018, 693) due to the absence of proper guidelines to acknowledge the labour. Based on these observations, in an effort to ensure the visibility of DLers in DH, we start by defining DLers in DH projects as any individual who is involved in DL during the developmental, dissemination, and/or maintenance stage of a DH project. DLers do not hail from a strict academic background, since, “in the whole field of social sciences and humanities research, most digital-related tasks are often assumed by under-considered technical staff or by technically inclined and qualified individuals working outside the realm of the university or at its peripheries” (Magis 2018, 161). Also, DH projects considered intelligent are often not equated with intellectual work, even though doing is as intellectual as thinking.

The next step is to understand the classification of DLers in DH projects, especially based on the labourers’ academic positions and the resulting hierarchy. The DLers in DH projects are broadly divided into academic and non-academic labourers. The academic labourers are further sub-categorized into faculty and students, where the former mostly consist of the PIs and the Co-PIs, along with the associated faculty members consulted as part of the project. The students, on the other hand, are the labourers who are expected to perform DL according to their academic position—graduate, post-graduate, doctoral, postdoctoral position, research associate, etc. The above categorization of the DLers in a DH project is shown in Figure 2. However, the scholarship on DH rarely addresses the issues of student labour and training, as “much of the scholarship related to students in DH focuses on pedagogy . . . but very little deals with students as collaborators or active participants in the projects whose success depends, to a great degree, on their labour. Indeed, as Daniel Powell et al. have recently observed, professional publications often fail to address the topic of how to train DH students for careers in DH” (Anderson et al. 2016). Therefore, this classification helps us not only to ensure the visibility of DL in DH projects, but also to foreground the double unrecognition faced by student DLers due to the positions they occupy in the academic hierarchy. (Double unrecognition is a phrase coined for our paper in emulation of the concept of double marginalization, given that DL itself is unrecognized in academia and that students’ efforts are similarly unacknowledged in the academic binaries of faculty and students.)

In this way, it is important to note that the fulfilment of the practical aspects of the field requires both time and effort that mostly go unrecognized and uncompensated. Therefore, the framework to address DL in DH projects should consider the training of the DLers involved, which should either be provided as part of the project development or granted for training from external sources. But for this, we require more funds. Anderson and colleagues note that the funding agencies perform a significant role in DH projects as collaborators (Anderson et al. 2016). Therefore, based on their surveys that evaluated the student training, funding constraints, and collaborative aspects within DH projects, which in turn intensify student DL, they conclude that “Students as labourers on DH projects are rarely acknowledged, whereas student labour on their own projects (outside of the classroom) is never mentioned” (Anderson et al. 2016).

There is a scarcity of research that exists on DL of students in DH projects, yet much of it, like that of Anderson and colleagues (Anderson et al. 2016), is applicable to the Indian context, as the problems that they discuss are universal due to the basic academic structure that prevails across the globe. Yet, in an effort to understand the specific problems faced by the Indian student DLers, we attempt this study to initiate further discussions on the same. We thus studied the projects on the primary level and then interviewed the persons online to have a behind-the-screen view of the project. For the projects, while exploring various social media platforms, we have also used our different linguistic backgrounds to facilitate the conversation. We realize, depending on the project type and context, that DL is not the same in every case. In this way, this paper, while analyzing the similarities of patterns (infrastructural support and lack of technical knowledge as so far found), has also tried to find out the dissimilar threads in their emergence and development of the field in the Indian context (raising the issue of recognition, also minimum wage).

The review thus brings forth questions against the ideals of the field, exposing the hierarchies that persist despite the field’s promises of openness, and narrates the circumstances of different DLers in the field. It lays bare the gap and calls for recognition of the labour in academia; particularly in the field of DH apart from other roles and responsibilities, there is a lack of proper definition of DL in the field, and thus our paper initiates a search for alternative models for compensation of the labour. While Woodcock considered labour in academia as part of “research, teaching, and administration,” noting its transformation into precarity through the herald of digitization and underlining the need for its recognition (Woodcock 2018, 135), our work focuses on a particular field that has seen radical shifts in welcoming the newer approaches of digital. Therefore, in an effort to recognize DL in the field of DH, this paper utilizes a case study of selected DH projects in India, categorizing them into government, academic institutional, and independent DH projects to analyze the visibility of DL. This would expose the gaps in the recognizability of DL in Indian DH projects. The paper analyzes the labour and probes some imperative questions on the field’s ideals, which have never been implemented properly in reality, nor initiatives taken to make it viable. In the literature review, the labour has mostly been talked about in the development of DH projects, but our present work focuses on DL not just behind the creation of the project, but also its sustenance (i.e., maintaining the website, updating the data, backing up, etc.), responsibilities which most DH students juggle alongside their day-to-day activities.

Thus, while Mann mentioned labour in academia in relation to these DH projects selected, he considered no single meaning or role for this labour but used it as an umbrella term for a number of “inextricable roles” (Mann 2019). So compensation as a standard wage or mere acknowledgment fails to serve/compensate the labour. Our paper does not probe into describing these complexities in the field or look for any pedagogical solution but asks for some logical and doable compensation of labour. Thus, proposing a more standard re-evaluation and nuanced structure means to find more acceptable forms of giving credit; our argument stands in finding more appropriate ways for “improving the effectiveness of academic labour” (Woodcock 2018, 132) and “giving fair and even generous credit to your digital humanities collaborators from all quarters of the academy [that] will make imaginative production, enthusiastic promotion, and committed preservation of DH work a shared and personal enterprise” (Nowviskie 2011).

3. Materials and methodology

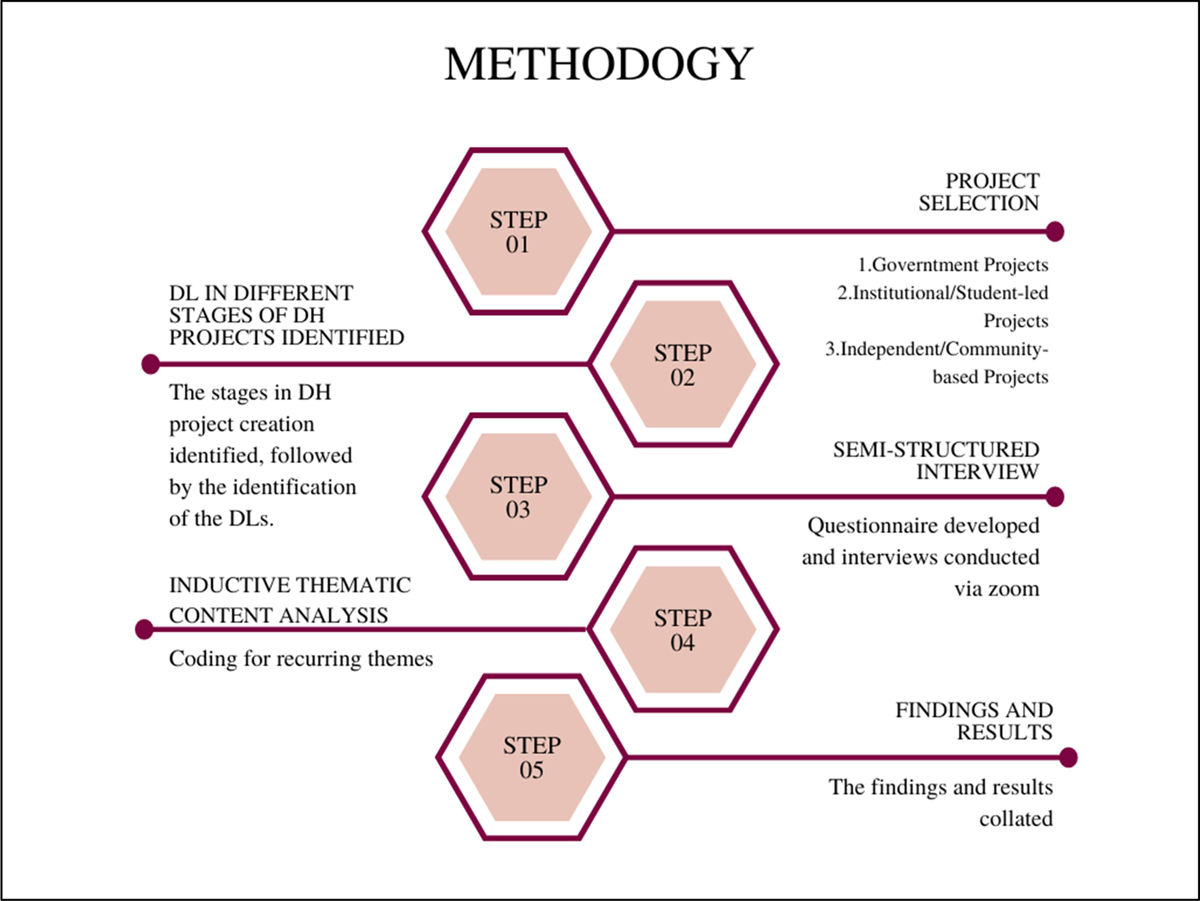

The methodology adopted is qualitative research (i.e., interview-based case studies). Firstly, we short-listed the DH projects feasible for this study (see Figure 3); however, we were able to connect with seven projects. We consciously identified smaller projects that were not as well known or well researched. We emailed the available contacts for responses to a questionnaire on their projects, focusing on their experiences with DLers. The selected DH projects were further classified based on the funding and collaboration into three groups: government projects; institutional or student-led projects (academic projects); and independent or community-based projects (led without any academic, institutional, or government funding and collaboration). We received and recorded the responses from two government projects (G1, G2), three institutional or student-led projects (S1, S2, S3), and two independent projects (I1, I2). For the sake of maintaining anonymity and objectivity in research, the DH projects are assigned abbreviations as evident in the previous sentence. We have endeavoured to incorporate projects from diverse fields and disciplines like literature, publishing, archiving, design, arts, and research repositories. The interviewees are also chosen from different academic and non-academic hierarchical positions with different levels of experience in DH—students mostly from postgraduate and doctoral levels (3), project leaders (2), founder (1), and scientist (1).

The Selected DH projects are:

G1 - Project Madurai (Govt)

G2 - Shodhganga (Govt)

S1 - Panchatantra Reloaded (Student)

S2 - KSHIP (Institutional)

S3 - Semiotics, Digital Archiving, and Emerging Artists from India (Student)

I1 - Design Beku (Independent)

I2 - Purple Pencil Project (Independent)

Secondly, the DLers in the different stages of DH projects are identified. We looked at websites and social media handles (if any) to identify the DLers in the three stages—development, dissemination, and maintenance (elaborated in detail in the previous section of the paper)—of the selected DH projects. Many have suggested a reframing of the traditional evaluation formula (Boyles et al. 2018; El Khatib et al. 2021). But our work investigates whether the evolving initiatives of evaluation frameworks are a noteworthy part of recognizing labour involved in the process. In rethinking the evaluation strategies in DH scholarship, Bethany Nowviskie proposed a turn from the evaluation of the “final outputs” to the process of production and reception of scholarship. In the production stage, the collaboration works in a sphere of complex human relationships with “status-based divisions among knowledge workers,” and reception is where the scholarship is “refactored, remade, and extended” (Nowviskie 2011). Thus, we are looking into the DL involved in the process of development, dissemination, and maintenance of DH projects.

Thirdly, the empirical data for the research is collected using semi-structured interviews, which form the basis for the case studies of selected DH projects in India. A questionnaire (see Annexure 2) addressing our basic research questions on DL is prepared, in which the interviewees are allowed to elaborate their opinions and observations. The methodology facilitates an open conversation with the project heads on the issues prevailing in India, especially with respect to acknowledging and compensating DL in DH.

Because of the diverse geographical locations of the interviewees, interviews were conducted online via Zoom, based upon participants’ availability and preference. The student-led projects were mostly focused to grasp a grassroot view of development of DH projects. The other major projects of DH in India (which are already studied and much written on) have also been analyzed in the study to support the argument. The qualitative, semi-structured, Zoom-based interview method is proven to be effective in enhancing the quality of the research by facilitating in-depth discussions and conversations (Gray et al. 2020). The participants were thus allowed to share histories, development processes, struggles within, and current position of their projects. We had substantive conversations, as we ensured that the discussion happened according to the availability and convenience of the participants. The concerns therefore that emerge from the conversations were diverse and cannot go behind a simple thematic categorization. The descriptions of labour were varied and project specific. The analysis consequently becomes twofold in identifying the different DLers involved in the projects of different stages and the forms of DL in the respective projects. The recorded Zoom interviews were therefore transcribed for inductive thematic content analysis. The transcribed interviews were subjected to coding, where common themes and patterns were identified to reveal the similarities and differences within the main categories and subcategories of codes.

The thematic content analysis further led to several important findings, which were later collated to propose a framework for acknowledging and compensating DL in Indian DH projects. The findings include:

DL in DH in India is subjective, owing to the diverse definitions that are given by the interviewees.

DL increases when digital work is not seen as valid academic output in the country until it gets substantiated with print materials.

Lack of DL acknowledgment and legislation for standard minimum wage for labour is manifold in DL.

There is an evident double labour with students working on DH projects with the challenges foregrounded above. Also, a close look will provide insights on the DL involved in DH projects. This labour varied in the three stages of development, dissemination, and maintenance in the analysis part (note here what Bethany Nowviskie stressed on introspection and evaluation of the process than the final product [Nowviskie 2011]).

While navigating various categories of DH projects, an evident privilege of technical knowledge, funding, and infrastructure according to the nature and context of the projects prevails. Conclusively, all the interviewees identified DL as a valid investigation in any DH project, and the discussion should come forward to make DL visible.

The analysis and findings are elaborated in the forthcoming sections.

4. Analysis

A variety of themes stemmed from our analysis of the interviews, such as technical knowledge, infrastructural support, manpower, funding, and a comparison pitting the Anglo-American and European countries against India among several others on the DL in DH. Our specific focus on the Indian context of DL in DH gave us multi-variegated perspectives on the concerned phenomena, which compelled us to consider the subjectivity in the definition of DL. We also found that though labour is integral to the field, the awareness, recognition, levels of precarity, and forms of compensation of DL differ across the selected projects. The findings therefore reveal the complexities in defining DL and DLers, the various factors contributing to this complexity, the contradictions in the fact-check between theory and reality of DL, and the limitations/privileges in terms of intellectual and material resources. The in-depth qualitative analysis of the projects has been able to reciprocate more than meets the eye. For instance, we found that the trajectories of the projects were different with some projects transforming and culminating into another form (G2). This often blurs the strict categorical boundaries among them.

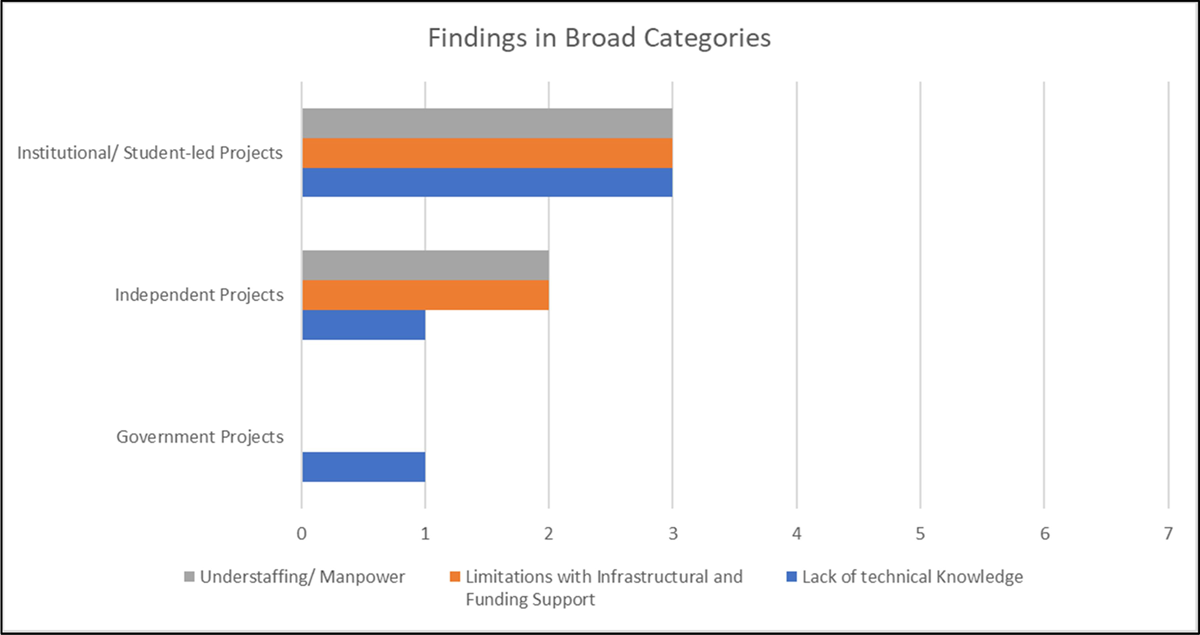

The primary aim of the interview analysis was to identify the DLers of the selected DH projects and the definition of DL for each project. For instance, for I2, even tweeting is DL. The DLers in the government projects are mostly research scholars with faculty members, university coordinators, staff, and students also acting as DLers. In the case of independent/community-based DH projects, the DLers are mostly professionals from web designing and technical backgrounds who were hired to perform the digital part of the content created by the traditional humanities scholars. Institutional/student-led projects mostly had student DLers (ranging from postdoctoral candidates to undergraduate students and research associates who performed most of the digital work). The second step of coding the major themes provides three broad categories, which are the limitations that the projects faced in terms of 1. manpower (understaffing), 2. technical knowledge, 3. infrastructural and funding support, which in turn increased the DL in DH projects. Due to the semi-structured nature of the interviews, we were also able to have elaborate discussions on other topics as well. Academic hierarchy is one such theme that burdened the student DLers, who are expected to perform much of the labour due to their lowest position in the line. Time constraints is another theme, as DH scholars are expected to deliver both theoretical and computational outputs. The subjectivity of the term DL is the next repeated theme, which consequently makes it difficult to define the same. The main themes and the sub-themes coded are elaborated in the forthcoming sections. The theme-based coding and categorization unpacks the unavailability and limitations present in the DH projects while mapping out the tedious DL and reveals the invisibility and precariousness of DL in DH. The major themes that emerged out of the analysis of the interviews are: 1. manpower (understaffing), 2. technical knowledge, 3. infrastructural and funding support.

4.1. Manpower (understaffing)

Manpower, a recurring concern raised by the DH project heads of I2 and G2, turned out to be a determining factor in both the development stage and maintenance stage of the DH projects. The relation between manpower and funds is pointed out by the I2 project head: “it is difficult to sustain if you do not have a monetary model around the project. We need enough funds to support the project. For instance, I needed a graphic designer at some point of the project but could not afford to have one.” While independent projects struggled in acquiring manpower due to lack of funds, the government project had the authority to demand compulsory DL from the students in the form of digitizing their thesis. Even with this evident privilege in acquiring manpower, the latter still struggled due to the unavailability of technically skilled experts to perform the advanced requirements of the project. The institutional or student projects also faced the problem of procuring manpower, mainly due to the lack of funds. The lack of manpower therefore burdened the students who were forced to acquire technical skills, along with the theoretical or analytical outputs that they were expected to produce. This is highlighted by the PI of S1 when the project is referred to as “solo-institutional project, that is part of the PhD thesis.” The independent community project, I1, on the other hand, acquired manpower according to the specific requirements of the projects and therefore hired temporary employees or volunteers from digital community platforms (Discord server). The independent projects also faced a funding crisis that was mostly overcome by shifting the medium of operation. For instance, I2 project head states: “with the lack of funds and manpower coupled with the pandemic, we are now focusing more on social media interaction for building a community (outreach). Even funds don’t work if you’re lacking manpower. We find it difficult to acquire regular freelancers who can review the platform and organize the contents into a form that attracts the attention of the readers.” The understaffing or lack of manpower is a specific challenge in DH as a transdisciplinary field because, while in the STEM fields the mechanism of the intersection between a project and a PhD is clearly defined and established, the same has not been done for the humanities and to some extent the social sciences. Therefore, there is a need to establish this mechanism in DH so that these transitions are transparent and comprehensible.

4.2. Technical knowledge

The traditional humanities scholars of the selected DH projects in general expressed their concerns over their lack of technical knowledge required for DH projects. Limited funding available to the institutional or student-led projects, which in turn led to a shortage of manpower, overburdened the few students who are working on the projects with DL. We also found that DL visibly differs between the humanities students with sufficient technical knowledge (as in S1 and I1) and students from pure humanities background (as in S3). To ameliorate this problem of technical knowledge, the government projects have been working with a huge circle of collaborators engendering the facilities of massive training programs (G2). The lack of technical knowledge is overcome by the independent projects through collaborating with other field experts who either join voluntarily (I1) or are hired (I2) to perform specific duties. The PI of S2 mentions the privileges that technical institutions like IITs (Indian Institute of Technology) had over other universities and institutions in acquiring technical skills: “The process of learning technical skills was difficult for the humanities students of the project, but we did seek help from the BTech and other technical students.” The PI of S1 goes a step further by stating “the need to provide humanities students with coding skills to lessen DL in DH and to save time.”

4.3. Infrastructural and funding support

Infrastructural support

The government DH projects enjoyed more infrastructural and funding support as compared to the independent and student-led projects, as the former is directly carried out by the government. We also found the disparities in funding and infrastructure within the educational institutions with DH projects. The traditional humanities departments like S1 (mostly English departments) found it more difficult to acquire infrastructure and funding as compared to humanities departments with an established DH centre, S2 and S3. The absence of funding led to a limited availability of infrastructure, which in turn reduced the training opportunities for DH students, leading to an increase in DL. The students are often forced to acquire the required infrastructure on their own, which also raises the question of economic privilege as evident in the words of the PI of S1, who created a DH project while working with a traditional English department: “I worked on a solo-institutional project as part of my PhD thesis, though I had scant prior technical knowledge. I set up infrastructure in my room, with no external funding, and worked with free versions of the websites and softwares. If I did not have the privilege of possessing minimum technical knowledge and were not able to self-fund, I would never take the same path.” The PI also noted the limitations in self-funding DH projects given that most DH tools are expensive. The PI of S1 also mentioned the struggles in setting up a DH centre and being part of the pioneer group with limited infrastructure, thereby increasing DL.

Funding

Funding crises are a major recurring problem cited by most of the PIs from all three categories. According to the PI of S3, “the lack of funding makes DL more intensive.” Thus, it is undeniable that the matter of acknowledgement and compensation of labour can be initiated with a stable funding facility. But following Anderson and colleagues (Anderseon et al. 2016), it is seen that the mega canonical (“Bichitra” on Rabindranath Tagore) digitization projects (National Digital Library [NDL]) are mostly successful in obtaining grants in the country (especially the ones with government support—G1, G2). The mega projects, which can show the project outcomes to the government funding agencies, are easily funded, as opposed to the smaller independent projects. This in turn limits the number of employees in a project, thereby increasing the DL. The student-led and independent projects, on the other hand, are mostly self-funded (S1, S3). Though the funding constraints and difficulties are no different from the Anglo-American countries in establishment of the field (S2), the new set of recently allotted fundings to various DH projects across the globe demonstrate an awakening towards the importance of the field and its work (DH Lab IIT Indore, NEH Digital Humanities).

4.4 Specific differences in DL (on the three themes) between the Anglo-American and the Indian context

The Anglo-American countries have vibrant academic support, faster internet, advanced technology, faster-hosting facilities, and faster server speed; so, running a one-person team becomes possible coupled with ample tech support and matching affordance (I2, S1): “Also, the better facilitation for procuring the tools required irrespective of their use makes the contrast vivid with India, where difficulty in purchasing the basic tools forces students to navigate through multiple free versions until they find the exact tool that best suits their research” (S3). The labour intensifies with the lack of any standard for minimum wage in the country (I2). Also, the Anglo-American countries have progressed in the digitization drive when compared to India where both the students (S3) as well as governmental (G1, G2) efforts are now working on equal footing on archiving and digitization projects for the establishment of the field in the country. Similarly, the PI of S3 mentions in the context of DL that “the lack of awareness and funding are the key markers that create the huge difference between the DL in India and the west.”

The PI of S3 also refers to the lack of funding that makes DL more intensive in India: “in the Anglo-American world they easily procure the tools required for DH research irrespective of whether it is actually used in the research or not. But in India, it is difficult to purchase the basic tools required, as they are expensive, which forces students to navigate through multiple free versions until they find the tool that best suits their research.” The lack of industrial participation in India with respect to funding research projects when compared to the other countries around the world is another striking difference that intensifies DL in India. Therefore, DH in India is still very much restricted to the realm of industry, technology, and people with interdisciplinary approaches (I1), a nascent stage engaged in digitization work. Therefore, only the prominent technical institutes in the country are found recognizably better with infrastructural support in comparison with other state and private institutions (S1, S3), which feeds into the reason for emergence of DH in the country through these technical institutes.

4.5. Comparison between the three groups

In terms of technical knowledge and manpower, we found that the government projects have an upper hand as they are able to secure collaborators and mandate contributions to the projects, as well as offer training programs. Infrastructural support was also more for the government projects compared to the independent and student-led projects. Understaffing (lack of manpower) and lack of funding/grants are serious setbacks faced by the academic/student-led projects compared to the independent and govt projects. The above-mentioned findings are evident in Figure 4. While some government (G2) and student-led projects (S1) mentioned the reluctance of the older-generation professors to accept DL as authentic academic labour, most student-led projects (S1, S3) claimed that “there is no DL in Indian DH projects,” as what the Indian DH scholars are doing is only preliminary groundwork, which has already been accomplished in Anglo-American countries three decades before (I2). Here rises the gap, which our paper highlights in having a standard strategy for recognizing and compensating DL (I2). Thus, in our analysis, we have narrativized suggestions that emerged from the participants for more appropriate ways of acknowledging labour, while emphasizing a standard compensation in finalizing a minimum wage, separating the required academic work/learning from the precarious engagement with labour.

4.6 Other findings

Similarly, comparisons with respect to privilege and funding between IITs and central/state universities is given by the PI of S1, whereas S3 PI compares two IITs—one with a DH cohort and the one without, as the struggles faced by the teams in the latter is more than the former. Both the PI of G2 and the PI of S1 mentioned the reluctance of the older-generation professors to accept DL as an authentic academic labour. The PI of I2 highlighted the absence of a DL compensation framework in India, “we don’t have a standard in compensating DL.” In another set of observations, scholars battling the challenges of infrastructures and funding are found discouraged by the DH projects’ relevance in the field where the degree-conferring process still depends on the print thesis (S1). The projects only substantiate print theses; support and recognition of the projects stand nowhere as a central part of the thesis-awarding process (S1). The thread of unrecognition is discouraging when projects are not admitted to be of importance in the hierarchy with written documents (I2, S1). In S2, the project head had to make sure that students go through similar close reading, along with the digital work, to stay relevant in the traditional evaluation system of humanities. These questions on relevance and institutional barriers have also driven the DH projects to emerge as independent without any association with universities (I1, I2). Thus, this resistance to accepting digital content as valid academic output marks the necessity in validation of DL and digital content in academia with a solid theoretical background.

For the research scholars the discouragement comes from various sources—first, the lack of technical knowledge, second, the limitations with infrastructures, and finally, the inferior hierarchical status and unavailability of space for having conversations on the development of the projects and reflecting the DL involved (I2, S1, S3). The shallow knowledge about DL left it unacknowledged at the project websites (S1, S3), along with the recognition of other labourers involved (S3). Hence, to initiate conversation on DL, one of the project heads (S3) intends to acknowledge DL involved in the upcoming thesis, highlighting the importance of the hands-on experience and stressing the time required for a “pure literature” student to learn and tweak the digital tools required. Also, a proposal for a chapter in the final thesis acknowledging DL comes with an and agreeable response (S2). Suggesting an alternative (I1) suggests that PhD students at this time should write less and do more, as with the field of DH, there is a lot to be done for the field to reach the level of development in the country. In DH we still overemphasize humanities rather than the digital (Anderson et al. 2016). Another alternative non-academic way of recognizing labour with social media platforms comes up through the conversations with independent projects (I1, I2). The suggestion and initiation of training programs specifically for humanities and social science students and teachers are also directed towards mitigation of challenges in achieving the goals and aimed at the inclusion of institutions. This becomes an important alternative for reducing labour in a way of eliminating lack of familiarity with digital (G2).

In this way, the study unpacks numerous conversations about the field, its emergence, and the hindrances in fulfilling the practical aspects—the conversations which may be known to every DH scholar in the country, but never put in such a manner. It reveals and initiates many open conversations on and about the field and the problematic labour, and proposes the future take-ons. In due course, we have thus realized that the recognition of the precarious labour is necessary and are hoping to propose a rethinking on possible ways of compensation.

4.7. Acknowledging and compensating DL in the selected DH projects

Some of the selected DH projects acknowledge DL in the following ways: S3 had a portfolio set up (for the artist), and for the PI, it served the purpose of digital archiving space as part of the coursework. Here the DL compensation was mutual. In terms of the DL compensation, apart from the portfolio creation, the project and the artist were acknowledged at a DH conference where the project received critical acclaim. According to the PI, “the artist actually used the project/medium as an initiation towards his portfolio.” For the S1 PI, the acknowledgement was part of the PhD thesis: “there is evidence of the website in the thesis; my thesis is based on the possibilities of creation of such a website. It has been acknowledged implicitly.”

5. Results and discussion: Proposal

The interview analysis and findings indicate the following major points:

Governmental or institutionally supported projects had an added advantage over independent projects in finding funds, collaborators, and infrastructural support, which in turn increased the DL in the latter.

The DH projects did not provide technical training support to the traditional humanities scholars who had to train themselves—a time-consuming, tedious labour in itself. One government project was already doing this.

There exists a general lack of awareness about DL; most of the interviewees are unaware of the concept of DL, which in turn led to overlooking the same.

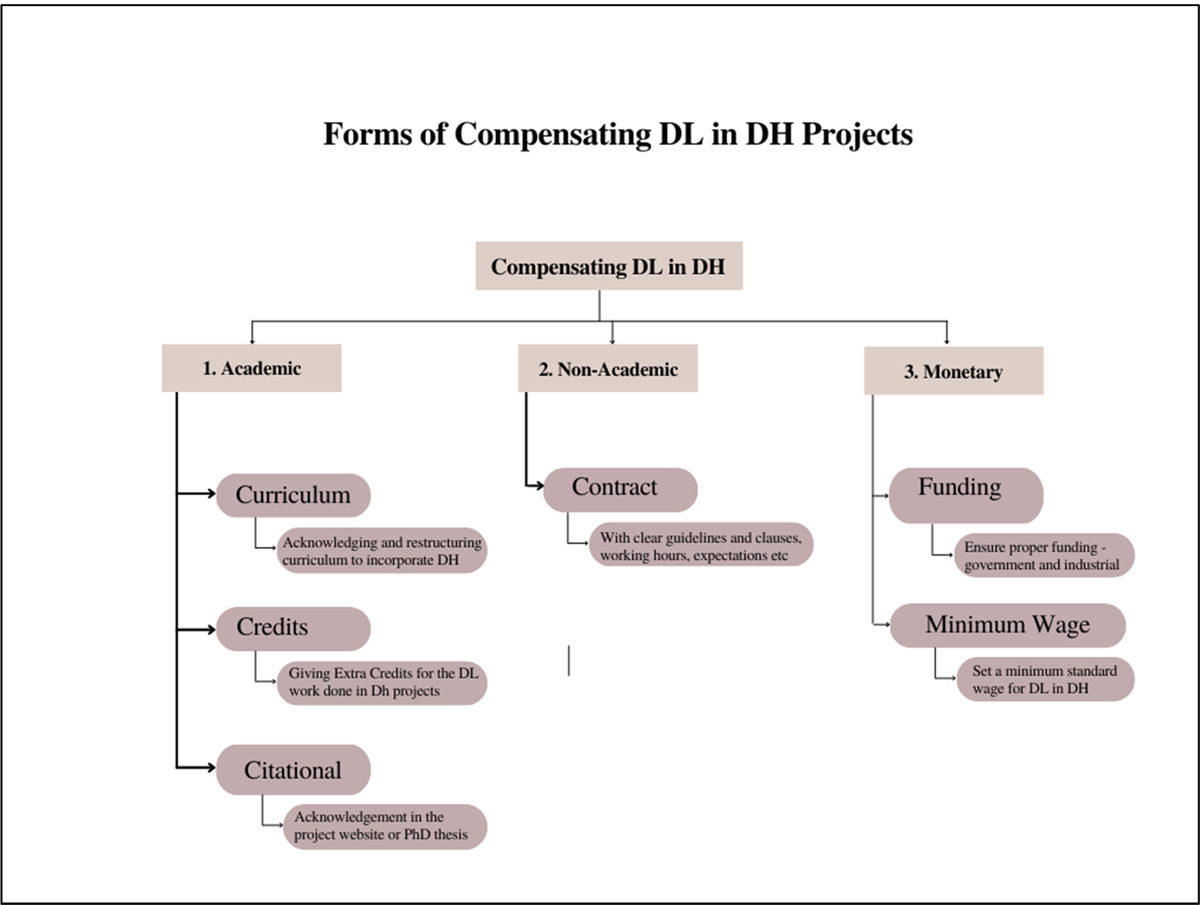

The observations and findings outlined above and in the analysis section, together with the suggestions put forward by our interviewees, helped us in proposing a possible framework for acknowledging, reducing, and compensating the DL in Indian DH projects. Such acknowledgements should come in useful in academic as well as non-academic formats. The solutions to the problems also accommodated a review of the previous works and their suggestions on renewal of the evaluation strategies in the field, along with a pedagogical overhaul to realize the field’s ideals. Figure 5 summarizes the different forms for compensating DL in DH that we propose in this paper.

The following proposals for reducing DL are applicable to the DH projects in general, irrespective of the categorization that we have followed in this paper. Funding agencies acting as prominent collaborators serve to pave the way for the students’ opportunities for training, possibilities for access, and skill development. An equal distribution of the funds will also improve and ensure an inclusive upliftment (in supporting the marginalized as well as canonical). Funding plays an essential role in many projects, as emphasized by many of the interviewees of our study. Boyles and colleagues state: “There must be continued and sustained investment from institutions of higher ed, independent of grant funds, toward human resources, rather than stopgaps for acquiring digital resources. In the end, it is always the skilled people and the communities they build who will sustain programs and projects” (Boyles et al. 2018, 698). Along with this, it is also important to ensure proper industrial participation in funding research in India so that both industries and academia can benefit from the same. Taking the cue from Anderson and colleagues (Anderson et al. 2016), we suggest that a proper fund flow and equal distribution of funds should be ensured to support DH projects, which can also consequently compensate DL. We also propose rigorous crowdsourcing and actual realistic collaborations (not just confined to papers theoretically) during the development and establishment process of the projects to reduce the DL.

The present funding ecosystem in India is unequal, as previously mentioned in the funding section (4.3). Agencies like ICSSR (Indian Council of Social Science Research), UGC (University Grants Commission), ICHR (Indian Council of Historical Research), ICPR (Indian Council of Philosophical Research), etc. cater to humanities and social sciences funding. But DH here is a fairly new field, so convincing the agencies about the field’s importance becomes challenging. Very recently, the Government of India has released NRF (National Research Foundation), which has become an umbrella body for funding research from various disciplines. Again, the challenge for the HSS students is to share the research findings that are at par with research needs, both digital and otherwise. In this context, NRF as a new ecosystem for funding is being created; it is imperative that there is a demarcation and definitive space for humanities research.

The traditional notions are restricted and hardly accommodate the new approaches of this emergent field. Also, the funding agencies for humanities and social sciences are far too few compared to the funding agencies of the STEM fields. Forty percent of students across the country pursue higher degrees in the former the funding ecosystem of the country, and this number barely accounts for the majority of research scholars. The lack of funding to the majority of research scholars compels them to heavily rely on free labour. The disparity of funding is not only based on the disciplines, but also based on the institutions (premiere institutions such as IITs and IIMs) and the projects (canonical projects) for which the funding is sought. The lack of flexibility in the usage of funds is another problem, which limits its usage for specific purposes. This requires us to build more and more trust with the Project PI, who most of the time tries to diversify the fund/make the most of it. Therefore, it is important to give the PIs flexibility to use the funding. Besides this, Indian academia in general faces a lack of funding. The system of funding should therefore be improved in order to decrease the labour. So, unless the system gets more efficient, the labour will continue to suffer. The casualty will always be the people at the bottom of the pyramid (the research scholars). DH is an emerging field working in the peripheries of the traditional disciplines and departments, and therefore it is still finding its grounding within the academic structure. This means access to funding, skill, and resources is always going to be more challenging. Added to that is the burden of persuading the agencies of the relevance and academic rigor and the labour-intensive work that goes into the conceptualization and implementation of even DH projects. And because of these challenges, even in smaller projects, the labour is huge, unless certain access to tools and resources is available.

Next, at the academic level, we suggest the upholding of introductory DH courses from the grassroots level to equip the traditional humanities scholars with the basic skills that are required to work in DH projects. At the legal level, we need an apt legislature to set up a standard minimum wage for DL in the Indian context, which could further be modified and adopted for DL in DH. During the interviews, it was also observed that there are no fixed working hours for the DLers working on DH projects; they are expected to work whenever they are required. Lack of fixed and accepted working hours in DL “can leave less time in the work week to devote to writing for scholarly publications and university presses, forms of labour that remain privileged components of many tenure and promotion review protocols” (Boyles et al. 2018, 695). Therefore, fixed time should be allotted to the DLers with some level of flexibility. It is also important to acknowledge DL as a valid academic work that can contribute to academic credits, promotion, wage hikes, etc. When it comes to students, student labour, training, and funding are interconnected (Anderson et al. 2016). Student labour is inversely proportional to training and funding. This labour decreases with more training sessions, which is further dependent on the availability of funds. Therefore, proper steps to address these interconnected factors should also be a primary concern of the PIs of the DH projects. To cite here, one of the project heads (S2) from the interviews mentioned giving the doctoral students the opportunity and encouragement to own the project output as first author.

The proposals for an academic format of acknowledging and compensating DL in DH projects primarily focuses on ensuring the visibility of DLers, especially student DLers, rather than viewing them as “unseen collaborator” (Clement 2013) and their work as “precarious” (Boyles et al. 2018, 693). Anderson and colleagues (Anderson et al. 2016) discuss this aspect and pose questions like “how can it [DL] be valued or leveraged when entering the job market?” but they do not suggest ways to address the same. The DL in DH projects should be seen as valid works that could be converted to academic credits or certificates. The students who perform DL in DH projects should either be awarded credits that can add to their coursework requirements, or they should be provided with a valid certificate detailing the skills that they have acquired and the DL that they have performed, both of which can aid them in their job application process. Financially compensating DL in every stage of a DH project is not feasible with the existing funding crisis in the field of humanities. Compensation can therefore come in different forms by taking into consideration both the availability of funds as well as the consent of the DLers. Compensation in the form of acknowledgment of the DL behind the project in the main DH website; establishing a minimum pay for the labourers; restructuring the DH curriculum to give credits to the DL done; and awarding certificates for the DLer in a project, which can add to career or academic credits, are some of the ways in which we can start thinking about compensating DL in DH in academia.

At the doctoral level, DH research scholars should be encouraged to include a thesis chapter to acknowledge DL (a separate section of the thesis of the DH scholars should acknowledge the DL in DH, along with their struggles in learning the required skills). Also, we propose a further detailed study on DL as an integral part of every DH project. and to publish this DL as a part of the DH project deliverables, something which we induced from our engagement with the DH projects that we interviewed. The proposals for a non-academic format of acknowledging and compensating DL in DH projects include framing a proper contract with clear guidelines and clauses to be signed between the employer (the project PIs in most cases) and the DL, which will ensure a set working pattern, time, trainings offered, requirements and expectations from the DLers, the stages of career (e.g., promotion, hike in wage, etc.), as well as the compensation that will be offered.

6. Conclusion

In this way, we started off with DL in academia in general and then started focusing on the field of DH. The conflation of digital with humanities leading to the field’s radical transformation has proposed various ideals endorsing the notions of openness and inclusivity. But our probe into the implementation process reveals the shift in labour (from traditional version) and its precarity and invisibility in unawareness. This reality check is not new and rather has been proposed by many, yet we found the DH projects in India grappling with similar challenges, largely understudied. Even our endeavour in defining DL by dividing the DH projects into different stages of development and identifying DLers in the respective phases of making the project has faced limitations in establishing any strict boundaries, as the phases are overlapping onto each other, and, in the case of independent and student-led projects, this division is again more difficult, with most of the works managed singlehandedly, spiking up the intensity of the labour. We acknowledge that we have not investigated all forms of DL in DH projects, for instance that of the PIs, as in this paper we focus only on the student DL. We have relied heavily on the solutions given by Anderson and colleagues (Anderson et al. 2016), which are more at a grassroots level and demand an overhaul from the core for having a greater change and better future for the field. Still the observations from the interviews indicate a visible privilege by the government and institutional DH projects, which were able to procure infrastructural, funding, and manpower support with less effort as compared to the student-led projects, which in turn reduced the DL in the former. We were also able to understand the different forms of DL involved in projects (academic and non-academic), and the prevalence of an academic hierarchy that shifts the major burden of DL to the students, as well as the reasons for the increase in DL. Such findings and observations enabled us to collate and propose a possible framework to acknowledge and compensate for the different forms of DL in DH towards the later section of the paper. The framework proposed is a work in progress that we hope will facilitate further discussions resulting in critiquing and expanding the same.

Annexure 1: Details of the selected DH projects.

| Project Name | Project URL | Project Category | Short Names |

| Panchatantra Reloaded | [this site was down at the time of the article’s publication] | Student | S1 |

| KSHIP | https://iitikship.iiti.ac.in/ | Institutional | S2 |

| Semiotics, digital archiving, and emerging artists from India | https://sites.iitgn.ac.in/digitalstudies/ | Student | S3 |

| Project Madurai | https://www.projectmadurai.org/ | Government | G1 |

| Shodhganga | https://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/ | Government | G2 |

| Design Beku | https://designbeku.in/ | Independent | I1 |

| Purple Pencil Project | https://www.purplepencilproject.com/ | Independent | I2 |

Annexure 2: Questionnaire

Tell us something about your DH project (conceptualization and implementation).

How many people were/are involved in the project (faculty members and students)?

Do you know about digital labour (DL)? What is the meaning of DL for you?

How have you documented or acknowledged DL in your project? If you could, share some reflections on DL from your journey.

Do you think DL is much more in the Indian context compared to the Anglo-American world? What were the major complications faced by you (for example, students’ technical knowledge, infrastructural support, institutional support, funding, and other criteria, if any)?

The students (if involved)—how did they overcome these complications and learn? Was it a difficult journey for them? What are their reflections on these?

Does the project website acknowledge, cite, or compensate DL?

What do you think about recognizing DL (Y/N)? Provide reasons for your answer. If “Yes,” how do you propose to do so?

Annexure 3: Selected responses of the interviewees

G1

On the lack of infrastructural support for the project in the initial stage:

The project started in 1998 January with no physical building for the work. It started off as a crowdsourcing project with people across the world generating the digital part; this an earliest Indian digital heritage project.

On the transition of the independent project into a government one:

I have more than 5000 texts in my project, and now we are making progress because the Tamil Nadu government has allocated 50 lakhs per year for the digitization process.

The project head acknowledges that the situation of DH projects across the globe is more or less same, as they all suffer with the problems of funding:

There is not much difference between India and the west; it is pretty much the same.

How the project acknowledges DL and the DLers:

When people use our text free of cost, as there are no price tags, we ask them to keep the front page with the DL[er]s names intact and not to remove it, no matter how the texts are used.

G2

On the labour faced by the government projects in the initial stage with infrastructural lack and funding constraints:

Digitization was not there when the project started. Internet speed was slow and expensive in the beginning. There was also lack of infrastructures and expertise at each university (except IISC, IITs) when we started this on a national level.

Government project mandating participation and ensuring sustained manpower:

Later the project aimed for metadata and full text digitized repository. In 2005 a guideline was made when universities were not responding equally, then it was made mandatory notification; that is the power of policy. It helps in expelling or at least minimizing the duplicacy of work within universities by providing a digital platform for repository.

On the lack of technical knowledge to make the output open and accessible:

Training is required, as students know how to create the content but not how to digitize it to make it accessible publicly.

On the lack of technical knowledge with humanities students:

In 2009 when the project started, we especially got entries from science discipline[s], as they know the process.

I1

The project head emphasizes the doing aspect of DH, as there is a lot to be done for India to reach the level in DH:

PhD students at this time should write less and do more. In DH we still overemphasize humanities rather than the digital; students are not making things; DH isn’t developing the way it should to match the pace; research is essential, but one cannot imagine DH without doing things.

The size of the group is very flexible, and the project is an open space:

They work from project to project; people come and go out according to their projects of interest; nobody is employed for time. Community on Discord server and also a group of volunteers.

The way of acknowledging DL for the project:

The specific project information is usually posted on the Discord server, and people are asked who wants to design for them. Then designers sign up, and the campaign happens. We are in the process of granting greeting certificates after completion of individual projects. Or their Instagrams are highlighted because most of them use their Instagram handles to show their work. This a part of acknowledging activity. Again, sometimes people just want to help collaterally.

I2

The conceptualization of the project and making the project independent of institutional barriers:

Did not start as a DH project, aim was to create a digital community and wordbook. The project was during the PhD, had the luxury of giving time. I didn’t think about the ethics, wanted it to be a business not a PhD thing, wanted it to be independent, not moving from institution to institution.

On the sheer amount of time and effort for uploading a post on WordPress (independent projects using/affording the simple software for their projects):

WordPress works slower and slower as you add more posts; as the database size of your website increases, it becomes heavier and takes a lot of time.

On the double labour:

There are two parts of labour—reading and writing the book review and putting the work on website.

Indicating the lack of funds:

It is difficult to sustain if you do not have a monetary model around it, needs enough funds to support the project.

The comparison:

India now digitizing a lot, putting things online; this is what has already been done in USA in the past 30 years, so we are facing the labour now in the lack of support.

On the intensity of the [digital] labour:

[Apart from reviewing,] putting it on WordPress, designing, organizing, attaching the suitable photograph . . . developing, designing, and managing website, managing the social media handles, are altogether additional tasks that one should engage him/herself with to make it efficient, popular and engaging.

On splitting the labour into manual and digital, and thus recognition of DL:

Reviewers are only paid for their manual labour; they are not asked to do anything else.

Her suggestion for recognition of digital labour is to talk about it in terms of absolute numbers, not as theories:

Creating a post takes hours, taking a photograph, uploading, circulating that on social media . . . it takes huge time.

The project voicing a standard minimum wage for India:

Minimum wage for labour is USA 30 dollars; we don’t have a standard.

S1

On the hierarchical division of DH projects and print thesis:

Essentially the PhD is awarded for the print, not for any accompanying digital material, because it is irrelevant for them. There is no provision in Indian government’s thesis-awarding procedure to look at a website and award a thesis. For me, the audience was a traditional thesis reviewing committee.

The acknowledgement of DL in theses:

There is evidence of the website in the thesis; my thesis is based on the possibilities of creation of such a website. It has been acknowledged implicitly.

On the lack of awareness and encouragement for recognition of DL in Indian DH projects:

The goal of my project was to produce a website showcasing the digital possibilities of Panchatantra as part of my thesis, and regarding DL, there was no audience for that kind of a conversation.

Developing skills is necessary for humanities students working with digital:

There is a need to provide humanities students with coding skills to make DL easier and to save time.

An independent student-led project without any external funding shows the signs of advantages for having technical knowledge and privileges of self-funding:

Created a tech-corner for myself.

The project head, though implicitly, acknowledged the privilege she had, yet was not spared by limitations. The project suffered from time constraints:

A lot of my time was spent in collecting materials, and very little time was left to do the actual process.

Indicates the nascent stage of DH field in India:

We have been in this road for the past ten years where everything only gets digitized and people getting excited about this. The digital work needs to go beyond manuscript coming on the screen.

S2

On the lack of recognition of DL in Indian academia:

The way the university system is structured, I am not confident that if you do a completely DH thesis . . . you would have to do as much close reading along with the digital work, because what if an external reviewer say that this is not good enough for a PhD?

The project head confesses the problems in acknowledging DL:

The difference between a traditional department and a DH department in acknowledging DL is due to the resistance in accepting digital content as valid academic output.

On the intra-country differences in infrastructural support for institutional DH projects:

In technical and infrastructural support, we are better because we are from an IIT. The process of learning technical skills was difficult for the students, but we did seek help from the B.Tech and other technical students.

Understanding the matter of funding as of utmost importance in compensating DL for the DH projects and putting in efforts to make that real:

I have worked with the governmental agencies in convincing them to allocate more resources to humanities, especially DH, so that DL could be more recognized.

The project head acknowledges gratitude to those PhD students who put their extra labour for the development of the project:

I owe them a big debt because they were doing it along with everything else.

She makes sure to recognize DL as part of PhD thesis in future:

I will make sure that there will be a chapter about the process of creating the digital content.

S3

The comparison of the field and labour between Anglo-American countries and India:

We need more professors in India for DH because in terms of DH in India, the awareness is very shallow.

On the lack of infrastructure and awareness of DL in the emergence of DH in India:

When it comes to DL in DH in India, it is important to address the confluence of humanities and the digital, but we are not doing enough to overcome the difficulties in learning and employing the digital tools.

On the lack of funding for DH projects:

Lack of popularity of DH courses leads to less funding, therefore more DL.

On the lack of technical knowledge in DH and unawareness of existing tools:

The DL in India is confined to archiving and digitizing, like lot many people do not know that the tool I am currently working on—Unity—also comes under DH.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Contributions

Authorial

Authorship in the byline is by magnitude of contribution. Author contributions, described using the NISO (National Information Standards Organization) CrediT taxonomy, are as follows:

Author name and initials:

Apsara Bala (AB)

Jyothi Justin (JJ)

Nimala Menon (NM)

Authors are listed in descending order by significance of contribution. The corresponding author is AB.

Conceptualization: AB

Data Curation: AB, JJ

Formal Analysis: AB

Investigation: AB

Methodology: JJ

Project Administration: AB, JJ, NM

Supervision: NM

Validation: NM

Writing – Original Draft: AB

Writing – Review & Editing: AB, JJ, NM

Editorial

Section Editor

Frank Onuh, The Journal Incubator, University of Lethbridge, Canada

Copy and Production Editor

Christa Avram, The Journal Incubator, University of Lethbridge, Canada

Layout Editor

A K M Iftekhar Khalid, The Journal Incubator, University of Lethbridge, Canada

References

Anderson, Katrina, Lindsey Bannister, Janey Dodd, Deanna Fong, Michelle Levy, and Lindsey Seatter. 2016. “Student Labor and Training in Digital Humanities.” Digital Humanities Quarterly 10(1). Accessed February 2, 2023. http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/10/1/000233/000233.html.

Boyles, Christina, Anne Cong-Huyen, Carrie Johnston, Jim McGrath, and Amanda Phillips. 2018. “Precarious Labor and the Digital Humanities.” American Quarterly 70(3): 693–700. Accessed February 2, 2024. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1353/aq.2018.0054.

Braunstein, Laura. 2017. “Open Stacks: Making DH Labor Visible.” dh+lib (June 7). Accessed February 2, 2024. https://acrl.ala.org/dh/2017/06/07/open-stacks-making-dh-labor-visible/.

Clement, Tanya. 2013. “Text Analysis, Data Mining, and Visualizations in Literary Scholarship.” In Literary Studies in the Digital Age: An Evolving Anthology, edited by Kenneth M. Price and Ray Siemens. Accessed February 2, 2024. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1632/lsda.2013.8.

Cohen, Daniel J., Stephen Ramsay, and Kathleen Fitzpatrick. 2013. “Open-Access and Scholarly Values: A Conversation.” In Hacking the Academy: New Approaches to Scholarship and Teaching from Digital Humanities, edited by Daniel J. Cohen and Tom Scheinfeldt, 39–47. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Accessed February 2, 2024. https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/166/oa_monograph/chapter/833156.

ECDS (Emory Center for Digital Scholarship) Team and LITS PMO (Libraries and Information Technology Services Project Management Office) Team. 2022. “Home.” PM4DH: Project Management for the Digital Humanities. Accessed February 2, 2024. https://scholarblogs.emory.edu/pm4dh/.

El Khatib, Randa, Reese Alexandra Irwin, Caroline Winter, and Michelle Levy. 2021. “Digital Doctorates.” Digital Studies 11(1). Accessed February 2, 2024. DOI: http://doi.org/10.16995/dscn.380.

Graham, Mark, and Mohammad Amir Anwar. 2017. “Digital Labor.” In Digital Geographies, edited by James Ash, Rob Kitchin, and Agnieszka Leszczynski. London: Sage Publications Ltd. Accessed February 2, 2024. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2991099.

Gray, Lisa, Gina Wong-Wylie, Gwen Rempel, and Karen Cook. 2020. “Expanding Qualitative Research Interviewing Strategies: Zoom Video Communications.” The Qualitative Report 25(5): 1292–1301. Accessed February 2, 2024. DOI: http://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2020.4212.

Greetham, David. 2012. “The Resistance to Digital Humanities.” In Debates in the Digital Humanities, edited by Matthew K. Gold, 438–451. Accessed February 2, 2024. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctttv8hq.28.

Jones, Paul. 2010. “Digital Labor in the Academic Context: Challenges for Academic Staff Associations.” Ephemera 10(3/4): 537–539. Accessed February 2, 2024. https://ephemerajournal.org/contribution/digital-labour-academic-context-challenges-academic-staff-associations.

Kim, Katherine. 2017. “Introducing the ‘Miracle Workers.’” Digital Library Federation (blog), December 15. Accessed February 2, 2024. https://www.diglib.org/introducing-miracle-workers-working-group/.

Magis, Christophe. 2018. “Manual Labor, Intellectual Labor and Digital (Academic) Labor. The Practice/Theory Debate in the Digital Humanities.” tripleC 16(1): 159–175. Accessed February 2, 2024. DOI: http://doi.org/10.31269/triplec.v16i1.847.

Mahony, Simon. 2018. “Cultural Diversity and the Digital Humanities.” Fudan Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences 11(3): 371–388. Accessed February 2, 2024. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/s40647-018-0216-0.

Mann, Rachel. 2019. “Paid to Do but Not to Think: Reevaluating the Role of Graduate Student Collaborators.” In Debates in the Digital Humanities 2019, edited by Matthew K. Gold and Lauren F. Klein, 268–278. Accessed February 2, 2024. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5749/j.ctvg251hk.25.

McGann, Jerome. 2014. A New Republic of Letters: Memory and Scholarship in the Age of Digital Reproduction. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Nowviskie, Bethany. 2011. “Where Credit Is Due.” Bethany Nowviskie (blog), May 31. Accessed February 2, 2024. http://nowviskie.org/2011/where-credit-is-due/.

Roy, Rianka. 2015. “Infinite Ways to Make Profit: Digital Labor and Surveillance on Social Networking Sites.” Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities 17(1): 43–57. Accessed February 2, 2024. https://rupkatha.com/digital-surveillance-social-networking-sites/.

Thangavel, Shanmugapriya, and Nirmala Menon. 2020. “Infrastructure and Social Interaction: Situated Research Practices in Digital Humanities in India.” Digital Humanities Quarterly 14(3). Accessed February 2, 2024. http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/14/3/000471/000471.html.

Woodcock, Jamie. 2018. “Digital Labor in the University: Understanding the Transformations of Academic Work in the UK.” tripleC 16(1): 129–142. Accessed February 2, 2024. DOI: http://doi.org/10.31269/triplec.v16i1.880.